Blog

For years, household electrification has been the holy grail of energy access. Dozens and dozens of studies begin by noting the tragedy of a billion people without electricity at home. Researchers then go on to analyze barriers to household electrification – be it through grid extension or with solar home systems – under the assumption that great things will come when the lights go on.

On some level, this intuition is correct. Without household electricity, life is drudgery. Even basic lighting sucks without electricity.

But the same is true of many basic necessities. Life is also drudgery without roads, schools, and hospitals. Life is drudgery without jobs and clean water.

For researchers, assessing the relative importance of household electrification, as compared to other development interventions, is thus critical. We need to know which interventions bring bang of the buck – and which are essentially money for nothing.

At the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP), we accepted the challenge and reviewed all statistically rigorous studies we could found published over the past two decades.

It was a heavy lift, and what we found was disturbing.

1. There are very few statistically rigorous studies focused on key outcomes.

If rural electrification is the need of the day and a hot topic, the academic community certainly has not yet noticed. We only found 31 studies that focused on evaluating the impact of household electrification on at least one of the following outcomes: business creation, education/studying, energy expenditure, household income/expenditure, and household savings.

This paucity of rigorous research is bad news for development policy. Although there are hundreds of case studies and industry reports, we were only able to find a handful of academic studies that made a serious effort to establish causality.

2. Different research methods produce wildly different results.

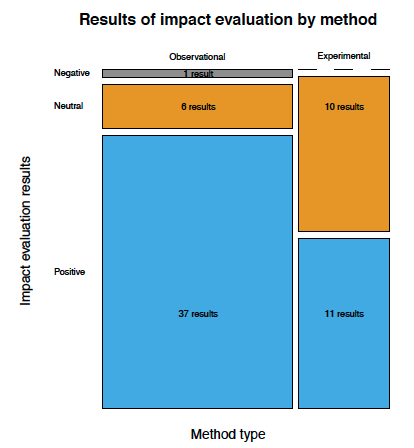

Want to argue there is at best modest impact? Go for a randomized controlled trial, following the lead of this year’s Nobelists. Want to argue that rural electrification has a large impact? Go for quasi-observational methods. Want something not too hot, not too cold? Go for a descriptive approach. As Figure 1 shows, one’s choice of method is strongly associated with the result. That is troubling, as method should not drive a substantive outcome.

It is impossible to say which method produces the correct result. The aforementioned Nobelists would defend randomized controlled trials, whereby households are randomly assigned to “treatment” (obtain electricity) and “control” (no electricity) groups, to the death. We mostly tend to agree, but trials have their own limitations, such as a common focus on off-grid technologies and a short time span. So let’s say we agree, but with a few caveats: trials need to be designed to consider effects over time and provide an abundant, affordable, and reliable source of power.

3. A geographic bias confuses and confounds us all.

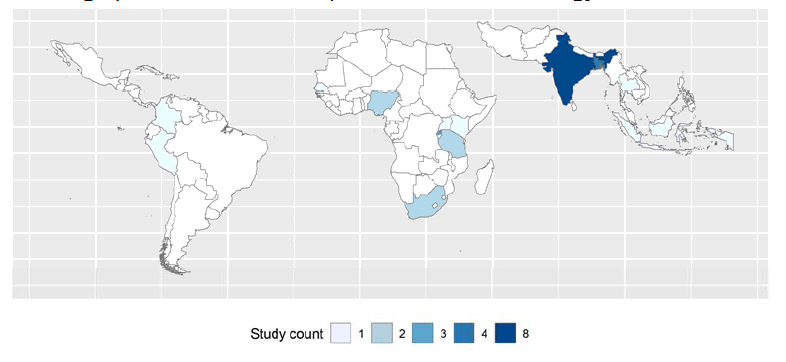

The general lack of studies is bad enough, but it gets worse when we consider geography. In another study, we show that impact evaluations of household electrification are heavily biased in favor of certain geographies (yes, Rwanda, I am looking at you). Most African countries do not have a single impact evaluation in them, even though this region has the vast majority of the world’s non-electrified households. Just look at Figure 2.

The bottom line is that energy access policy is mostly made based on intuition, instead of data. The global development community needs to either stop the pretense of evidence-based policy or roll out a far larger number of carefully designed studies, with results communicated to governments and development agencies. Of particular import would be studies with multiple sites, ideally across several countries.

***

Johannes Urpelainen is the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz Professor of Energy, Resources and Environment (ERE) at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also the Director of the ERE Program and the Founding Director of the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP).