Blog

India’s power sector is undergoing a great transition from a heavy reliance on coal toward modern renewables, notably solar power. However, this transition remains subject to great uncertainties.

How fast can India reduce the use of coal without sacrificing the vitally important reliability of power supply? While the only correct answer to this question is that nobody really knows, here I offer three important facts to inform the analysis.

- India’s coal-fired power generation plants only run 60% of the time on average.

The Central Electricity Authority of India keeps track of how often thermal power plants were utilized. In the 2018-2019 financial year, this number was 61%. Reasons for this poor performance include problems with coal supply, non-payment by distribution companies, technical problems, and rules that give priority to renewable energy over coal.

Based on earlier experiences in India, this number could reach 85% in theory. If India were to fully exploit its coal-fired power generation capacities, total generation could increase by forty percent. No new plants would have to be built, except to replace retiring plants.

- Renewable generation costs continue to fall, but intermittency is an increasingly a serious problem for wind and solar power.

Renewable power generation is cheaper than ever. Government tenders encourage aggressive bidding in a large a growing market, as India aims to reach 225 gigawatts of renewable power generation capacity by 2022 – more than current coal-fired power generation capacity. According to Brookings India, solar projects now promise to sell electricity at INR 2.5 / kWh (USD 0.036 / kWh). No wonder renewable project developers now win the vast majority of government tenders.

The problem is that intermittent renewable energy introduces additional costs. The electric grid needs to deal with intermittent, fluctuating supply of solar and wind power. The same Brookings India report cites another study by the Central Electricity Authority, and puts the cost of this intermittency at INR 1.5 / kWh (USD 0.022 / kWh). For every dollar spent on power generation, another 60 cents are needed to deal with intermittency. While this specific number is subject to great uncertainties, the bigger point stands: intermittency, not generation cost, is increasingly the key issue for renewables in India.

- Government plans foresee rapid growth in renewable electricity supply alongside modest growth in coal-fired power generation.

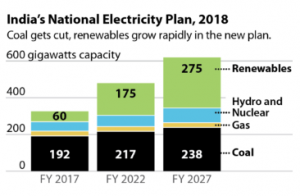

A neat summary of India’s electricity planning by IIEFA shows how the 2018 National Electricity Plan deals with growing electricity demand. Renewables capacity would reach 275 gigawatts, while coal would increase from below 200 gigawatts to about 240 gigawatts. While renewable growth would dominate capacity additions, gradual expansion of coal-fired power generation capacity would continue.

Taken together, these three facts lead to the conclusion that coal-fired power generation will continue to grow in India until 2030, but only slowly. There is little need for new capacity construction, except to replace retiring plants. However, current plants will continue to increase their generation as electricity demand grows.

Low renewable generation costs do not change this conclusion. Wind and solar power are increasingly constrained by the intermittency problem, and their ability to displace existing coal depends mostly on new solutions to this problem. Besides battery storage, possible approaches include improved transmission capacity, demand side management, and flexible coal-fired power plants that ramp up and down depending on renewable energy supply.

The government’s plans, then, are a plausible baseline. They recognize the growth potential of renewables but also avoid excessive optimism.

Photo credits: asianpower.com, ieefa.org.

***

Johannes Urpelainen is the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz Professor and Director of Energy, Resources and Environment at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also the Founding Director of the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP).