Blog

The International Energy Agency’s recent Energy Access Outlook examines the future of energy access by looking at scenarios for household electrification and access to clean cooking fuels by 2030. The central premise of the report, New Policies, is the IEA’s primary reference, and considers the impact of both existing and announced energy access policies.

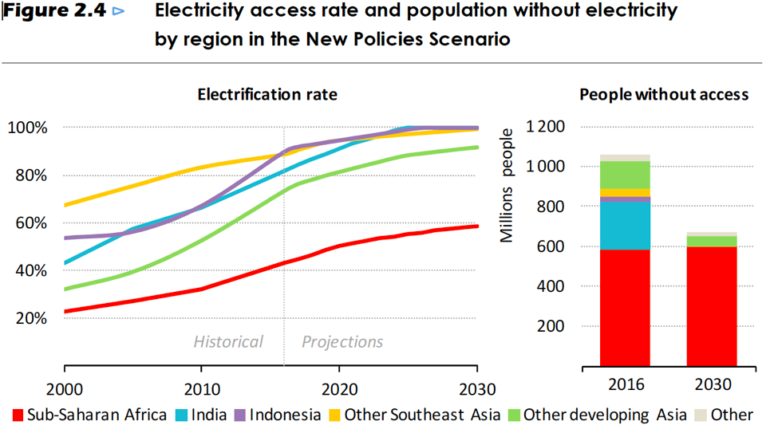

In this scenario, the future of electricity access can be summarized with two simple statements:

- Thanks to rapid progress in India and other countries, Asia achieves near-universal household electrification by 2030.

- In Sub-Saharan Africa, progress in electrification is mixed, as electrification rates continue to increase but the total number of non-electrified households also grows with population.

In Asia by 2030, only 54 million people (less than 1% of total population) will be without electricity. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the number grows from today’s 588 million (48% of total population) to 602 million (36% of total population).

The nature of rural electrification will also change. Only half of all new electricity connections will be to the electric grid, while the other half comes from mini-grids and micro-grids. This departure from total dominance of grid extension reflects both improvements in distributed power generation and the simple fact that many non-electrified households today live in sparsely populated areas that are difficult to connect to the grid.

For policymakers, the IEA’s predictions have three major implications. The first is Africa’s growing non-electrified population. The New Policies scenario is a far cry from modern energy for all, and governments need to adopt much more aggressive policies if they are serious about Sustainable Development Goal 7.

The second implication is the changing nature of energy access. The growing role of micro-grids that only provide basic energy access such as lighting, air circulation, and television means that many of the electrified households will not have access to productive loads to power the economy. While such basic energy access is important for daily life, a recent policy brief by the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP) shows that basic energy access produces few economic benefits beyond improved lighting and reduced energy expenditures. IEA’s reference scenario leaves open the question of how electricity access can contribute to economic growth.

Finally, Asia’s success in household electrification means that electricity access will increasingly be about affordability and reliability. The 2015 ACCESS survey shows that in India’s energy-poor states, for example, the quality of electricity access remains very low. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have not only struggled to electrify households, but also supply fewer than ten hours per day to households with electricity access. For electricity access to play a meaningful role in rural development in Asia, issues of affordability and quality must be front and center.

IEA’s Energy Access Outlook reaffirms that the challenge of household electrification is less about connectivity at the global level, and more one of supplying rural households with affordable and reliable power. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region of the world that will face a connectivity problem in 2030, and even there the challenge of moving beyond basic energy access is already emerging.

Image from IEA’s New Policies Scenario from the 2017 Energy Access Outlook.