Blog

Energy companies all over the world are constantly strategizing about whether, if not when, their operations will be expropriated by host governments. At the same time, major petroleum discoveries in emerging producers like Guyana and Mozambique have political leaders questioning whether or not to seize control of these lucrative assets.

While energy expropriation can offer immediate gains for those doing the taking, recent examples such as Argentina’s seizure of Repsol-YPF highlight just how costly these nationalizations can be. Retaliation in the form of international arbitration can drain the government’s legal resources (and bank accounts), expropriation can scare away foreign investment, and the technical inability to develop new reserves can stymie long-term revenues.

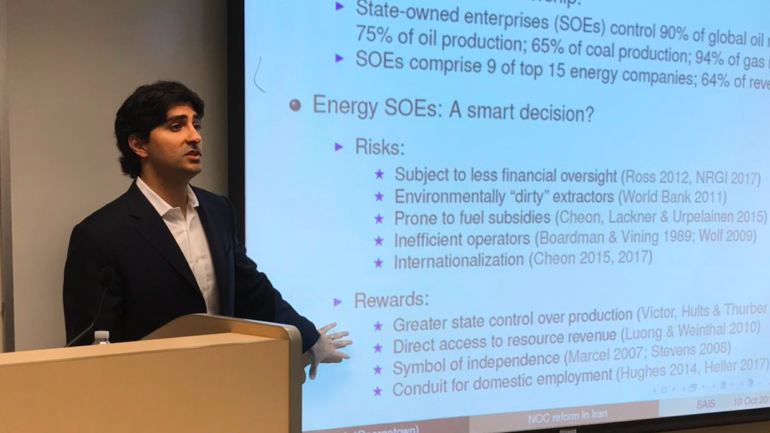

If these costs are well-known to leaders, then why do governments continue to nationalize energy resources? Are there different “types” of nationalization that offer leaders greater rewards in light of these risks? In a recent talk at Johns Hopkins SAIS, sponsored by the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policy, I presented four points of interest for leaders considering expropriation and for firms on the other side of the negotiating table.

- Leaders nationalize when they see others getting better deals.

There are a number of reasons that lead governments down the path of nationalization, ranging from the political value of controlling the commanding heights of the economy to the financial value of potential windfalls from high oil prices.

My research shows that the timing of nationalization is also about perceptions: leaders will nationalize when they perceive that revenues are not being shared fairly between host governments and private extractors. What they consider to be “fair” depends on what kinds of deals their competitors—that is, leaders in other resource-producing countries—are getting from the extractive companies.

For example, back in 1971 the Shah of Iran came to an agreement with Western oil companies to increase their income tax rate to the Iranian government. At the time, the Shah viewed the deal not as a complete success but still fair in light of what other oil-exporting governments received. Yet the ink was still drying when the oil companies struck an agreement with Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the Emirates that promised an even better deal for the Arab states. Incensed, the Shah demanded a new arrangement. As negotiations escalated, the Shah ultimately seized complete control over operations and re-nationalized the oil sector in 1973.

- Not all nationalizations are the same.

Upon nationalizing, governments establish state-owned enterprises to handle the extractive sector. Yet there is considerable variation in what these enterprises actually do.

In countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, state-owned oil companies are in complete control of operations. The only roles available to outside firms come in the form of fee-based contracts for specific tasks. In places such as Angola and Kazakhstan, state-owned companies are involved in production but do not operate the majority of their countries’ fields—leaving most of the work to the likes of ExxonMobil, Shell, and Chevron.

On the other hand, national oil companies in countries such as Nigeria and Brunei play little to no role in the actual production of oil, but rather serve as overseers of extractive companies. These companies play the part of regulators, with no ability to get involved in operations.

At the extreme end are countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the government nationalized oil in 1999 but set up a state-owned enterprise that effectively does nothing other than collect taxes and royalties from private producing companies. Such a national oil company is quite the misnomer: it neither produces oil, nor is it really a company.

- Nationalizing production means more money, but it also brings new risks.

Across the spectrum of all oil-producing countries, I find that those with national oil companies that are in charge of production provide greater revenues to the state compared to other ownership structures, including private development.

Part of the reason why stems from a government’s ability to tax the state-owned company at higher rates than it can from private firms (who can choose to exit the market if taxes are too high). Part also stems from the notion that private firms might be hiding the true costs of production, thereby under-reporting profits and taxes. Giving control over operations to a state-owned enterprise narrows this informational gap, because the government has many tools at its disposal to pressure the enterprise to accurately report costs and profits. This means more money for the government’s coffers.

But others have shown that nationalizing the production of energy resources leads to operational inefficiencies and lower levels of extraction over time. Much of this is due to decreased competition and the lack of incentives for innovative techniques to squeeze more out of the ground with less money. Ultimately, while the government’s share of the revenue pie increases after nationalization, the pie itself might be shrinking.

- The future of nationalization will be more “indirect”.

Combined with the risks of international retaliation after expropriations, such operational inefficiencies have prompted a different tactic for leaders seeking greater state involvement in the extractive sector.

Instead of full-blown expropriation, emerging producers such as Kenya and Ghana have opted for what is called “back-in participation”. Here, the state pays off costs incurred by operating companies after discoveries are made, in exchange for shares of new production. This kind of “indirect expropriation” allows firms more flexibility in negotiating the terms of state involvement, but questions remain as to the legality of such actions in international courts.

Given the risks and rewards to nationalization, how should states and firms proceed? Building trust is essential to assuaging negative perceptions of fairness in revenue-sharing. The more that firms are able to involve the government in the process, the more likely governments are to trust that firms are accurately reporting costs and profits. As energy expert Valérie Marcel has pointed out, informal side-by-side partnerships are one way to do this. Secondment programs, allowing government officials to sit in on technical meetings, and frequent skills transfers are practical options for extractive firms seeking to operate in emerging resource-producing countries.

This is a win-win for both host governments and extractive firms. Governments may not capture maximum profits, but can rely on a steady stream of revenues while also promoting future investments in the sector. And extractive companies will find a renewed sense of confidence for a long and uninterrupted future in operations. While this kind of arrangement can lead to indirect expropriation, it can stave off outright nationalization—and the legal and financial