Blog

Political Institutions and Pollution: Evidence from Coal-Fired Power Generation – Three Facts

It is often assumed that more democratic nations are better at combating climate change and pursuing renewable energy solutions. However, the empirical evidence concerning the relationship between political institutions and fossil fuel use is fairly indecisive.

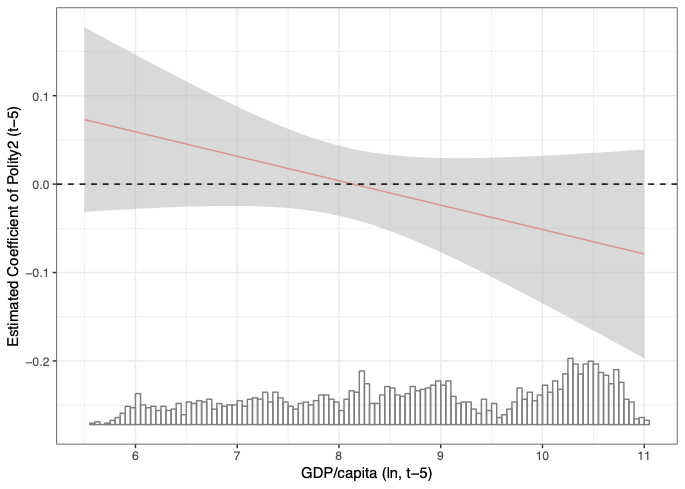

What is the relationship between political institutions and air pollution generated by the power sector? The short answer is it depends – specifically, whether democracies are more or less likely to utilize coal depends on their level of economic development.

Poor democracies are more likely to build coal plants than their autocratic counterparts.

When poor countries become more democratic or move from autocracy to democracy, they tend to commission additional coal power plants. This is because newly minted democracies must appeal to an electorate that craves economic growth and access to affordable energy. Electrification in particular is desirable for developing populations. Governments utilize coal-fired power plants to pursue cheap electrification and stimulate economic growth.

Rich democracies shy away from coal.

As countries become more developed, the population turns its attention from basic needs like income and energy access to pollution. Clean air becomes a more salient issue for the public once income levels are sufficiently high. In this sense, environmental protections are somewhat of a luxury good for citizens, and governments are responsive to the priorities of their electorate.

Political institutions mediate the applicability of the environmental Kuznets curve to coal.

The environmental Kuznets curve holds that natural resource usage and environmental degradation increase during the initial stages of development, with improvements to follow in the later stages. We suggest that this relationship should only hold in democratic countries, as democratic political institutions are necessary for the will of the public to be translated into policy. We introduce a new data set on coal-fired power plants commissioned between 1980 and 2016 in 71 countries to test whether this logic holds for coal-fired power generation. We find that it does.

In a country with a GDP per capita of $400, a movement of one unit along the 21-point Polity scale – a popular measure of democracy – increases a country’s expected coal plant capacity by about six percent, while an equivalent increase in Polity for a country with a GDP per capita of $22,000 reduces commissioned capacity by five percent in expectation. Democracy appears to begin having a negative relationship with coal power at a GDP per capita in the area of $4,000. The same gradual democratization pace in a country that is a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), regarded as a club for rich countries, reduces the amount of coal power capacity added in expectation by roughly 13 percent, while it has a weakly positive association with coal capacity in non-OECD members.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the relationship between democracy and coal-fired power generation is more complicated than is often assumed. Only rich democracies are better than their autocratic counterparts when it comes to curbing fossil fuel usage and mitigating climate change. In contrast, poor democracies are actually worse, as they sacrifice environmental quality for the economic growth and energy access that their public desire.

Richard Clark and Noah Zucker are the Student Fellows at the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP)

Johannes Urpelainen is the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz Professor and Director of Energy, Resources and Environment at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also the Founding Director of the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP).